Misinformation Resources

As librarians, it is our duty to help our patrons discern fact from fiction by adequately meeting the information needs of our diverse community, both online and in person. Each month we are providing guidance on how to identify fake news, find and analyze reliable sources, evaluate your own biases, and consult with experts and fact-checkers to support the reliability of your sources. Together, we can move beyond fake news and into a new era of information literacy for all.

AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference

AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference

Arvind Narayanan & Sayash Kapoor

Princeton University Press, 2024

In AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference, Princeton computer science professor Arvind Narayanan and PhD candidate Sayash Kapoor take a clear, no-nonsense look at the world of artificial intelligence. They aim to help readers sort out what AI can genuinely do from what’s been overhyped. The authors compare today’s AI buzz to old-fashioned snake oil, those so-called miracle cures once sold by traveling salesmen, and argue that many modern AI tools, especially predictive ones, often fall short of their promises. These systems, they explain, can be unreliable, biased, or fundamentally flawed.

At the same time, Narayanan and Kapoor give credit where it’s due, acknowledging the impressive (if still imperfect) progress in generative AI while urging caution about doomsday predictions of superintelligent machines. Throughout the book, they lay out a practical, approachable framework for understanding AI’s real strengths and limitations. The biggest dangers, they argue, don’t come from rogue machines but from the way humans misuse these tools, overlook their flaws, or inflate expectations. AI Snake Oil encourages a smarter, more honest conversation about artificial intelligence, one focused on facts over spectacle, and accountability over hype.

Visit our online catalog to reserve a copy of AI Snake Oil

AI In The News

AI In The News

AI has been in the news a lot lately. Some of it’s cool, some of it’s morally grey, and some is, frankly, a little scary. With the pace of developments showing no signs of slowing down, we figured it’s a good time for a quick update.

This month, we’re looking at some of the most talked-about developments in AI: Google’s latest chatbot announcement, new debates over AI’s role in military decision-making in Gaza, and the growing conversation about AI’s societal risks. Alongside these headlines, it’s worth remembering that as AI advances, so does the potential for misinformation, whether through AI-generated content or confusion about what these tools can actually do. As the AI conversation races ahead, staying grounded in facts is more essential than ever.

1.) Google introduces their new A.I. Chatbot

In an attempt to keep up with competition from newer, more popular AI tools like ChatGPT, Google just announced a big change to how its search engine works. It’s called A.I Mode, and instead of just showing a list of website links, this new tool will let people ask questions, follow up with more questions, and get detailed answers directly from Google’s artificial intelligence system. You can think of it as a really smart digital assistant that’s built right into the search. Even with this updated experience, it’s important to remember that AI can still provide inaccurate, misleading, or unexpected information, so users should double-check answers and use trusted sources when it matters most.

2.) New bill raises concerns over state authority on tech rules

A small section in a recent bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives is raising alarms among some experts, who warn it could significantly weaken states’ ability to regulate technology. Although it’s framed as a 10-year pause on new AI rules, critics say the language is so broad it could prevent states from holding companies accountable for tech-related harms. The result, they warn, could be confusion, reduced consumer protections, and serious limits on states’ power to govern in the digital age. It’s a development worth keeping an eye on as the bill moves forward.

3.) AI deployment in Gaza raises ethical concerns

In late 2023, Israel used an AI-powered audio tool to locate and assassinate Hamas commander Ibrahim Biari, an operation that also killed over 125 civilians. The tool was just one example of how Israel has rapidly tested and deployed AI-backed military technologies during the Gaza conflict. In recent months, the country has integrated AI into facial recognition systems, target selection processes, and Arabic-language chatbots for analyzing messages and social media. While these technologies accelerated military operations, they also led to mistaken arrests, civilian deaths, and growing concerns about the ethical consequences of AI on the battlefield. As AI continues to shape military strategy, the risk of serious errors and unintended harm remains a critical issue.

Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies into Reality

Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies into Reality

Renee DiResta

2024

When Renee DiResta, a new mother to a 12-month-old, first began to research preschool options for her child, she was stunned to discover the widespread use of “personal belief” exemptions on vaccination records in California schools. It was a revelation that propelled her into action. When she contacted her local state assembly representative, she was told that the anti-vaccine movement was too well-organized and there was “no appetite for a fight over school vaccine opt-outs” (2). As DiResta immersed herself in the movement to combat vaccine misinformation and reduce vaccine hesitancy, she grew increasingly aware of what she refers to as a “new system of persuasion,” one driven by influencers, algorithms, and the audiences they cultivate. This system was reshaping how we consume information, decide who to trust, and interact with one another online.

Invisible Rulers examines the transformation of power and influence in the digital age, where propagandists use algorithms and online communities to manufacture reality. These actors, often perceived as grassroots voices, are in fact highly influential, using algorithms and social media to erode trust in institutions and reshape public opinion. DiResta reveals how this system has destabilized democracy, allowing misinformation to override facts and leaders to be undermined with ease. However, she also offers insights into how society can recognize and counteract these forces, providing a roadmap for restoring trust and legitimacy in a rapidly shifting information landscape.

“Anyone trying to create change in the world needs to understand the field they’re playing on, and Invisible Rulers will open your eyes to the nature of a game most of us don’t even realize we’re playing. DiResta provides a roadmap not only for concerned individuals, but also for our institutions, who need to step up. Invisible Rulers is required reading.”

– Jennifer Pahlka, former US deputy chief technology officer

Visit our online catalog to reserve a copy of Invisible Rulers.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

United States Constitution, Amendment Fourteen

On July 9, 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States was ratified to grant citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the United States, regardless of the citizenship or immigration status of their parents. During the tumultuous period of Reconstruction that followed the American Civil War, it was determined that all children would obtain citizenship at birth in accordance with the legal principle of jus soli, or “right of the soil.” The ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment was a direct response to the landmark Dred Scott v. Sandford case of 1857, which ruled that the U.S. Constitution did not extend citizenship to those of African descent.

Despite its long-standing legal precedent, misinformation regarding the legitimacy of birthright citizenship has begun to circulate widely online. Fueled by political debates about immigration and border security, misunderstandings, myths, and outright falsehoods about birthright citizenship have dominated public discourse in recent weeks. This month, we aim to separate fact from fiction by addressing the most widespread misconceptions about the Fourteenth Amendment and the principle of birthright citizenship. By clarifying these misconceptions, we hope to foster a more informed and accurate discussion on this constitutional right.

1.) U.S. is the only country with unrestricted birthright citizenship

Currently, around 30 countries including Mexico and Canada offer automatic, unrestricted citizenship to anyone born in the country. Additionally, some countries offer citizenship with restrictions, such as requiring one parent to be a citizen. While it is true that countries with birthright citizenship are the minority, they still represent a significant portion of the world and play a crucial role in shaping global migration policies.

2.) Revoking birthright citizenship from the children of immigrants would decrease illegal immigration

The concept of birthright citizenship has led to the widespread myth that immigrants come to the United States to have children who will protect them from deportation, regardless of their immigration status. Children born to undocumented immigrants in the U.S. are often referred to as “anchor babies,” but the citizenship status of their families remains far from secure. While these children are granted citizenship under jus soli, their parents can still be deported.

When the children of immigrants reach 21 years of age, they can sponsor their parents for a green card. However, they must prove that they can financially support their parents to ensure they do not become a financial burden on the public. In many cases, the parents may be required to leave the United States for up to a decade before they are eligible to return through the sponsorship process. Additionally, they cannot apply for naturalization until they have held a green card for at least five years.

3.) Birthright citizenship is not covered by the 14th Amendment because of the words ‘subject to the jurisdiction thereof.’

The Citizenship Clause’s provision stating “subject to the jurisdiction” implies some uncertainty about who should be eligible for citizenship by birth, but the 1898 ruling of the United States v. Wong Kim Ark settled that debate well over a century ago. Born to Chinese parents in the United States, Wong Kim Ark frequently traveled to China for temporary visits. In 1890, Wong Kim Ark was denied reentry to the United States under the Chinese Exclusion Act, which declared that the Chinese were permanently barred from becoming United States citizens. In a 6-2 decision of the Supreme Court, it was determined that Ark was granted U.S. citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment which could not be superseded by the Chinese Exclusion Act. This seminal decision reaffirmed the enduring principle of birthright citizenship and set a lasting precedent for its protection under the U.S. Constitution.

To learn more about birthright citizenship, check out this fact sheet from the American Immigration Council.

With winter in full swing, respiratory viruses like the flu, RSV, and the common cold are reaching their peak, thriving in indoor gatherings with poor ventilation and decreased air circulation. While seasonal infections surge offline, another epidemic is spreading online: medical misinformation. TikTok, in particular, has become a hub for misleading health advice, leaving users vulnerable to viral trends in addition to actual viruses. A recent study from the University of Chicago’s Biological Sciences Division revealed that nearly 50 percent of the videos they sampled contained inaccurate information. The rise in inaccurate videos about various health conditions, their treatment, and prevention can not only confuse the public but also spark trends that could result in harmful health outcomes.

If you’ve been a longtime reader, you might recall that we discussed the topic of medical misinformation back in June of 2023. At the time, one of the most widely circulated claims was that strep throat could be cured with potato juice. It cannot—and as many medical professionals quickly pointed out, untreated strep throat can become life-threatening without prompt antibiotic treatment. This year, we’re shoving whole cloves of garlic up our noses. Not quite as dangerous as untreated Strep A, but certainly not recommended by healthcare professionals. UChicago medical student, Rose Dimitroyannis, explains that inserting garlic into the nose to relieve congestion may appear effective because it causes more mucus to be expelled. However, this is simply an illusion; the garlic irritates the nasal passages, triggering increased mucus production. While a clove of garlic up the nose is unlikely to end in death, it might very well make your symptoms worse.

While the study from UChicago highlights a concerning amount of misinformation, researchers acknowledge that not all medical content on TikTok is inaccurate. They reported that medical professionals generally received high scores for video quality, factual information, and harm/benefit comparisons. As we navigate the challenge of managing misinformation in the Digital Age, we must learn to work with social media rather than against it. Instead of discouraging people from consuming medical information online, we should be encouraging them to seek out credible, credentialed medical influencers instead of relying on laypeople. Additionally, individuals should consult their own healthcare professionals before acting on any medical advice they encounter online.

In September of 2024, TikTok partnered with the World Health Organization’s Fides Group to limit health misinformation on the app. Fides is a network of healthcare influencers that have joined together to create trustworthy health content and fight misinformation by promoting evidence-based health content. Many medical influencers, such as neurosurgeon Betsy H. Grunch (@ladyspinedoc), pediatric ER physician Dr. Beachgem (@beachgem10), labor and delivery nurse Jen Hamilton (@_jen_hamilton_), and others provide reliable health information and help combat the misinformation and disinformation circulating on TikTok and other social media platforms. Empowering users to discern fact from fiction and amplifying the voices of trusted medical professionals are crucial steps toward fostering a healthier, more informed society—both online and offline.

Read the UChicago Study for free: A Social Media Quality Review of Popular Sinusitis Videos on TikTok

Learn more about Fides: World Health Organization (WHO)

The Web We Weave: Why We Must Reclaim the Internet from Moguls, Misanthropes, and Moral Panic

Jeff Jarvis, 2024

“The net and AI are tools, like the printing press and steam, the transmitter and the automobile, at once magnificent and perilous, which we may use to good ends and bad – with no certainty as to which will prevail.”

In an era where the internet faces growing scrutiny, Jeff Jarvis offers a fresh perspective on the challenges and opportunities of the digital age. The Web We Weave confronts accusations leveled against the internet—that it enables the spread of misinformation, divides us, invades our privacy, dumbs us down, and corrupts our youth—while urging readers to look deeper into the human behaviors and biases driving these issues. Jarvis argues that the internet is not the villain we often make it out to be, but rather a reflection of our own society, complete with its flaws and potential for progress.

In The Web We Weave, Jarvis challenges reactionary calls for heavy regulation and explores how we can better harness the web to foster meaningful community, creativity, and conversation. With optimism and insight, Jarvis paints a bold picture of a future where the internet becomes a force for good—a tool that works for everyone, not just those in power.

“Jarvis brings our history and current moment into sharp focus to argue that if we can renew our sense of collective obligation – which we have the power to do – we might just be able to reclaim the internet’s promise.”

Charlton Mcllwain, New York University

Visit our online catalog to reserve a copy of The Web We Weave.

On the evening of Thursday, September 26, Hurricane Helene made landfall on Florida’s Gulf Coast, where a massive storm surge and torrential rainfall devastated coastal communities and caused catastrophic flooding throughout Georgia and the Carolinas. With a death toll of 230 people and rising, Helene is the deadliest hurricane to make landfall in the United States since Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

On the evening of Thursday, September 26, Hurricane Helene made landfall on Florida’s Gulf Coast, where a massive storm surge and torrential rainfall devastated coastal communities and caused catastrophic flooding throughout Georgia and the Carolinas. With a death toll of 230 people and rising, Helene is the deadliest hurricane to make landfall in the United States since Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

In the wake of Helene, rumors, misinformation, and falsehoods about the federal government’s response have spread widely, particularly regarding funding for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). These false claims have significantly impeded disaster relief efforts, disrupting communication between survivors in need of assistance and FEMA. In this article, we will address and debunk three of the most widely circulated false claims about disaster relief efforts following this devastating storm. In times like these, it is crucial for us to come together with empathy and support for those affected, ensuring that accurate information and compassion guide our recovery efforts.

1.) Funding for the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) disaster response was diverted to support migrant populations

As Hurricane Helene battered the southeastern United States, rumors that disaster relief funds had been “stolen” and redirected to pay for social immigration services and programs began to take root. FEMA quickly countered that these claims are entirely false. Disaster relief is not FEMA’s only function. In addition to disaster relief, FEMA operates an initiative called the Shelter and Services program, created by Congress in 2023, which provides grant funding to nonfederal organizations that support migrants. The Shelter and Services program is funded by Congress separately from FEMA’s disaster relief fund.

Unfortunately, these rumors have deterred many hurricane survivors from seeking disaster assistance, as they believe that sufficient funding is not available for them. FEMA encourages those affected by Hurricane Helene to apply for assistance on their website, “as there is a variety of help available for different needs.” More recently, misinformation related to Hurricane Helene has incited violence against FEMA workers. Over the weekend, an armed North Carolina man was arrested for threatening FEMA employees working in the Lake Lure and Chimney Rock area, forcing the agency to temporarily pause aid in several communities.

2.) Storm victims will only receive $750 in federal aid

Hurricane survivors in declared disaster areas are eligible for a $750 FEMA payment called Serious Needs Assistance. The $750 payment can be delivered via direct deposit or a preloaded debit card and is intended to cover immediate needs such as baby formula, clothing, food, and fuel. It is not a loan. FEMA has explained that the $750 payment is only the beginning of the aid that recipients will receive from the agency in the months to come. This payment is designed to help those affected by Helene survive in the immediate aftermath of the storm. More than 1 million households have already been approved for over $780.7 million in Serious Needs Assistance (FEMA). Those affected by Hurricane Helene are also eligible for a wide range of relief programs, including shelter assistance and funeral assistance.

3.) State and Federal officials are hindering the flow of volunteers and donations in hard-hit areas

This is an example of misinformation that, while not entirely false, is still misleading. FEMA donations are not being “confiscated,” and volunteers are not being turned away; however, they are being asked to coordinate through state and federal relief agencies to ensure the safest, most efficient response possible. Similarly, they are not confiscating financial donations but rather urging donors to contribute solely to vetted volunteer organizations. This approach aims to protect against scams and ensure that funds are directed to established organizations equipped with the infrastructure and capacity to respond quickly and effectively. Emergency supplies are delivered to affected states by FEMA, where they are distributed to those in need by groups such as the North Carolina Air National Guard. FEMA, as well as local leaders in several affected states, have repeatedly refuted these claims and continue to plead with the public to stop spreading misinformation about hurricane relief.

As communities grapple with the devastating impacts of this catastrophic storm, it is vital to dispel misinformation that can hinder assistance and exacerbate the suffering of those affected. We used FactCheck.org, NPR Fact Check, FEMA fact sheets, and Poynter to verify the information in this article. Consistent fact-checking prevents the spread of misinformation and ensures that you are informed with accurate and reliable details.

November 5th is on the horizon, and disinformation campaigns are sweeping through headlines and social media feeds like wildfire. Over the next two months, we believe the best use of this platform is to highlight and disarm false information that has recently gone viral online, much of it targeting immigrants and refugees. This type of online activity fuels prejudice, hinders access to essential services, and creates an environment of fear and mistrust, jeopardizing the safety and well-being of our city’s diverse population of immigrants who provide invaluable contributions to our community. In this article we debunk three viral misinformation claims that have been dominating headlines in previous weeks. All of these claims highlight the critical importance of fact-checking and demonstrate how easy it can be to find authoritative evidence with a few clicks of a keyboard.

1. Haitian immigrants are consuming pets and wildlife in Springfield, OH

Last week, a viral narrative began circulating several social media platforms claiming that Haitian immigrants living in the town of Springfield, OH have been stealing and eating pets and other wildlife such as geese and ducks. Despite statements given by Springfield police and officials refuting these allegations, this dangerous false narrative persists. Several days after the claim went viral, police body cam footage showing a woman being placed under arrest for killing and eating a cat began circulating. Accompanying captions largely purported that the arrest was made in Springfield and that the perpetrator is a Haitian immigrant. Neither of those claims is true. In fact, the arrest did not take place in Springfield, but in Canton, OH. Furthermore, the woman being arrested is an American citizen who was born in the United States and grew up in Canton.

While it is true that the town of Springfield has seen a substantial rise in Haitian immigrants since 2020, their residence in the United States is not illegal. Citizens of Haiti living in the United States have been eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) since 2011, which allows them to obtain employment authorization and remain in the United States. By the end of the twenty-teens, the growth of manufacturing and corporations in Springfield created a sizable job deficit. As word spread within the Haitian community, the city experienced an influx of immigrants, all of whom now play a significant role in the local economy, filling much-needed jobs across sectors ranging from industry to healthcare. Springfield City Manager Bryan Heck commented, “It is disappointing that some of the narrative surrounding our city has been skewed by misinformation circulating on social media and further amplified by political rhetoric.”

2. Boar’s Head deadly listeria outbreak was caused by refugees

Last month, the popular high-end deli brand, Boar’s Head, recalled over 7 million pounds of meat after a listeria outbreak at their Virginia plant caused the death of 9Americans and the hospitalization of nearly 60. Days after word of the recall spread, posts began appearing on social media claiming that the outbreak was caused by refugees. One post on X was accompanied by a screenshot showing that Boar’s Head was a member of the Tent Coalition for Refugees in the United States.

Tent spokesperson, Haiwen Langworth, told PolitiFact that Tent is an organization that works with companies to employ “refugees and other forcibly displaced people who arrive under a variety of legal immigration statuses.” Though Boar’s Head was listed as a Tent partner, a spokesperson from the company stated that they only explored Tent’s services and ultimately decided not to work with them. Tent confirmed that Boar’s Head has never hired any refugees through its services (PolitiFact). The outbreak was simply the consequence of persistent health and safety violations at Boar’s Head’s Jarratt, Virginia plant, including the presence of insects, mold, and mildew.

3. Venezuelan gangs have taken over an apartment building in Aurora, Colorado

In recent weeks, rumors that the Tren de Aragua gang has taken over an apartment building in a Colorado town have been circulating widely on social media. This claim has been used to substantiate a widespread sensationalist narrative that migrants bring crime and violence into the United States on a large scale. Rumors about rampant Venezuelan gang activity have been supported by a very common (and very debunkable) mis- and dis-information tactic: fabricating a narrative by reposting old photos and videos with false or misleading context (News Literacy Project).

This particular narrative began with a series of health and safety violations related to three apartment complexes dating back to 2021. These violations included pest infestations, unsafe infrastructure, sewage backups, and leaks. Facing charges in municipal court as a result of their negligence, the property management company blamed the dilapidated condition of the buildings on a Venezuelan gang that had allegedly taken control over the properties by force. Aurora police confirmed that they have been investigating the presence of several members of Tren de Aragua, but stress that criminal activity has been very isolated and limited to ten gang members, nearly all of whom have been arrested.

Mayor of Aurora, Mike Coffman, recently released a statement on Tren de Aragua on social media. In it he stresses that the city has not been “taken over” as many have claimed. “TdA has not ‘taken over’ the city. The overrated claims fueled by social media and through select news organizations are simply not true.” Despite statements denying allegations of widespread gang violence from various authorities on the ground, the rumors persist. Most recently, claims that the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club is heading to Aurora to take down Tren de Aragua have begun popping up across social media platforms. One of these videos shows a popular bike rally in Sturgis, South Dakota in 2023. The Rocky Mountain Charter of the Hells Angels publicly stated that the claims were false.

We used PolitiFact, Reuters, and Snopes to verify the information in this article, and we encourage you to do some fact-checking as well! Consistent fact-checking prevents the spread of misinformation and ensures that you’re informed with accurate and reliable details. Happy sleuthing!

The right to vote is a fundamental pillar of American democracy, but the complex history of voting rights in the United States reflects broader struggles for equality and justice. From the early days of the Republic, when voting was largely restricted to White landowning men, to the landmark civil rights movements of the 20th century that bravely fought to expand the right to vote to all citizens, the journey toward universal suffrage is both a testament to the resilience of democratic ideals and an unsettling reminder of the ongoing challenges to achieving true equality at the ballot box.

Recent presidential elections have been marked by intense political tension, resulting in an uptick in the propagation of misinformation that aims to undermine public confidence in democratic elections and suppress voter turnout. Despite widespread claims that mass voter fraud took place in 2020, there is negligible evidence that supports these theories, many of which target people of color and other historically marginalized communities. With another election quickly approaching, it is more important than ever that we dispel myths about voting rights and election fraud.

Myth #1: Absentee voting, voting by mail, and public drop boxes allow for mass voter fraud

Since the American Civil War, mail ballots have been used as a mechanism to allow military and other overseas voters to participate in elections. The COVID-19 pandemic greatly increased the use of mail-in ballots due to health concerns and quarantine restrictions, but even as early as 2010, roughly one out of every four ballots cast were sent by mail (Election Assistance Commission).

In the 150 years since mail ballots were first introduced (yes, 150 years), state jurisdictions have developed a wide range of security features to protect ballots cast by mail from fraud. In addition to the standard hand-marked paper ballots and sealed envelopes, many states have implemented secure drop-off locations monitored by designated election staff. Drop boxes include locks and tamper-evident seals and may be secured to immovable objects to prevent theft. Video surveillance is often used to ensure that drop boxes in unstaffed areas are not tampered with. In addition, voters can track ballots throughout the shipping process much like you may track a FedEx package (National Conference of State Legislators).

Mail ballots are also kept secure in terms of physical handling during the collection process. Bipartisan teams are sent to retrieve ballots from drop sites and work together to verify signatures, open envelopes, prepare ballots for scanning, and participate in the counting process (National Conference of State Legislators).

Myth #2: Dead people can vote

Widespread allegations of “dead voters” were a trend in 2020, but the truth is that there are very few documented cases in which votes have been cast in the name of a deceased individual. More often than not, so-called “evidence” of dead voter fraud can be attributed to flawed comparisons between death records and voter rolls. Most states routinely check public death records and remove dead voters from rolls. There are also several instances of alleged voter fraud in which it was found that the voter died after casting a mail ballot.

In 2020, a study conducted by Andrew Hall, a political science professor at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, showed that out of over 4.5 million voter records from the State of Washington, only 14 cases showed evidence that a ballot may have been stolen and submitted by someone that died. This amounts to about 0.0003 percent of all voters over an 8-year period, which is hardly an election-swaying statistic.

Myth #3: Noncitizens can vote

Noncitizens have also become the target of widespread voter fraud accusations, but again, there is little to no evidence that this is true. Here, it is important to ask, why? Illegally voting in a federal election can result in deportation, revocation of legal status, and denial of future immigration status (Bipartisan Policy Center). Most would agree that this is a pretty severe price to pay for a single vote. Similarly to “dead voters,” most instances of alleged voter fraud by noncitizens can be explained by inaccurate list comparisons and common clerical errors. A recent study conducted by the Heritage Foundation found only 24 instances of noncitizen voting between 2003 and 2023. Once again, this number is nowhere near significant enough to impact the outcome of an election.

Myth #4: Double voting is a common practice

Again, documented cases of double voting are exceptionally rare. The Voting Rights Act prohibits individuals from voting more than once. A person convicted of double voting faces a fine of up to $10,000, a maximum of 5 years in prison, or both. (National Conference of State Legislators). A joint study out of Stanford, Harvard, Microsoft Research, and the University of Pennsylvania estimates that only 1 in 4,000 votes cast in 2012 were double votes. Additionally, they believe that a measurement error in voter turnout records is to blame for most of, if not all, of this discrepancy, meaning that no voter fraud actually occurred (American Political Science Review).

In the coming months, it is critical that we watch out for misinformation regarding voter fraud and voting rights. To learn more about the history of voting rights, visit the exhibit “Who Can Vote? A Brief History of Voting Rights in the United States” on display in the Otis Library Atrium! This exhibit is on loan from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History through the month of August.

The word “deepfake” is used frequently when discussing media, but what does it even mean? Let’s break the word into pieces:

Deep – which stands for “deep learning.” This refers to machine learning that uses multilayered neural networks to simulate the human brain. Forms of deep learning are used to power AI applications, from Siri to ChatGPT. The “deep” in deepfake refers to media that has been created by artificial intelligence.

Fake – falsified and artificial. The use of “fake” in deepfake requires the content of the media be incorrect or inaccurate.

Putting the two parts together, we can define a deepfake as a piece of media that was created or manipulated using Artificial Intelligence to appear real. The practice of media manipulation is not new. From the early days of photography, people would pose strategically to alter perspective (no one is truly holding up the Leaning Tower of Pisa), artists would cut and glue film to create new images, and, more recently, computer programs allow even the most inexperienced users to enhance or alter media. So why is the concept of a deepfake so concerning?

In its early inception, it wasn’t. This technology has been used for years in art and entertainment. The movie industry uses it to age an actor’s appearance, younger or older depending on the role. Multiple social media and photo editing apps use it for face and gender swap filters.

As technology has become equally more advanced and user-friendly, creator intent has changed. Silly selfies have been exchanged for misinformation and propaganda. Deepfake technology has been used to create images of celebrities in compromising positions, audio of political leaders discouraging people from voting, and scams that use recordings of relatives to ask for money.

As technology advances, it is getting harder to tell whether media has been manipulated. SpotDeepFakes.org is working to educate and empower people to combat deepfakes. This website will teach you about deepfake technology, including how to tell if media has been manipulated. At the end, you’ll challenge your skills by identifying manipulated photos and video. After walking through their exercises, you’ll feel more confident evaluating photos, video, and audio.

The 2024 presidential election is just 6 months away, and the internet has been a scary place. News is traveling at warp speed, social media feeds are overflowing, and a single click can send us through a labyrinth of contradictory information. Fact-checking is more important now than ever, but we also need to devise a realistic strategy to protect ourselves from harmful misinformation. At this stage of the game, it is simply not feasible for us to fact check every single news article or social media post. But the best defense is a good offense, and fortunately there’s a powerful tool at our disposal to navigate this chaotic landscape: strong research skills. Proactive yet cautious self-guided learning is a fantastic way for digital citizens to sift through the noise and stay ahead of misinformation.

We need knowledge to fight misinformation, but knowledge is expensive. Though open access journals are becoming more prevalent, a sizable portion of peer-reviewed literature lives behind a paywall. Fortunately, we have libraries to supply us with reliable, authoritative information at no cost! Listed below are several valuable education and learning resources offered by Otis Library. In the fight against misinformation, research skills are your shield and sword. Use them wisely, and together we can create a more informed and empowered online community.

History Reference Center

- Articles, reference books, primary sources, and biographies

Thousands of topics to help you explore ancient, world, and U.S. history - Teacher resources that support state and national curriculum standards

- Google Classroom Integration

ResearchIT CT

- Academic and scholarly resources

- Primary resources

- Newspapers

Science Reference Source

- Reference books, articles, and videos

- Biographies of scientists

- Over 2,500 lesson plans for teachers

- Includes topics ranging from the solar system to forensics

Legal Information Source

- Thousands of printable forms such as rental agreements, wills, patent applications, power of attorney, and more

- Access to full reference books from NOLO, the oldest and most respected provider of legal information

- Support for small business and financial literacy

Visit our Education & Learning Resources page to access the above databases and more! All Otis Library patrons can login from home with a library card. Public computers are available for in-library use.

The internet is a fantastic place to learn and connect, but as we know all too well, it can also be a jungle of misleading information. Children and teens are especially vulnerable to falling for misinformation online. With their critical thinking skills still under construction, it is often more difficult for kids to judge the truthfulness of what they see, often leading to anxiety and confusion as they encounter information that they can’t quite make sense of. Misinformation can also impact their health decisions, body image, and even their views on others. But fear not, knowledge is power! It is crucial that we teach young people how to be responsible consumers of information. Listed below are some awesome resources to help your children and teens become misinformation-fighting machines.

At Otis:

Think for Yourself: The Ultimate Guide to Critical Thinking in an Age of Information Overload and Misinformation by Andrea Debbink and Aaron Meshon (Ages 11 – 14)

Trending: How and Why Stuff Gets Popular by Kira Vermond and Clayton Hanmer (Ages 8 – 12)

Gimme Shelter: Misadventures and Misinformation by Doreen Cronin and Stephen Gilpin (Ages 7 – 10)

On Hoopla:

Knowing What Sources to Trust by Meghan Green (Ages 10 – 13)

Information Literacy in the Digital Age by Laura Perdew (Ages 13 – 17)

Deception: Real or Fake News? by Dona Herweck Rice (Ages 9 – 12)

Find out Firsthand by Kristin Fontichiaro (Ages 8 – 10)

Getting Around Online by Kristin Fontichiaro (Ages 8 – 10)

Fake Over (Spanish) by Nereida Carrillo (Ages 12+)

Fake News at Newton High by Amanda Vink (Ages 9 – 12)

Other Digital Resources:

PBS LearningMedia l NOVA: Misinformation Nation (Grades 6 -8; 9-12)

Scientific information is shared through the news, advertisements, and social media platforms by sources with differing intentions and levels of expertise. Unfortunately, science misinformation, information that contradicts what established science tells us to be true, can mislead and confuse people and potentially endanger their health and well-being. Learn the science behind why misinformation is shared, why it’s believed, and what we can do to address its spread across digital media.

PBS LearningMedia l Common Sense Education: Identifying “Fake” News (Grades 6 -8; 9-12)

What is “fake” news? How do we know it’s false? Use these resources from Common Sense Education to help students investigate the way information is presented so that they can analyze what they read and see on the Web.

internetmatters.org l Find the Fake Quiz (All ages)

Select an age-appropriate quiz to play as a family (parents versus children) to learn and test your knowledge on what fake news, disinformation, and misinformation is and how to stop it from spreading.

BBC Bitesize l Other Side of the Story (Teens)

Learn to spot fake news, break out of your echo chamber, and listen to every side of the story.

News Literacy Project l Misinfo 101 (Teens)

“Misinfo 101,” available on the News Literacy Project’s Checkology virtual classroom, is laser-focused on building students’ critical thinking and misinformation-busting skills.

It’s hard to believe that in just seven months, Americans will be lining up to cast their ballots in another presidential election. As exciting as elections are, we know that staying informed during this time can feel exceptionally overwhelming. As we are inundated with a constant stream of headlines, social media posts, and competing narratives, our brains may struggle to process and analyze information and our ability to distinguish fact from fiction can be impacted. Thankfully, organizations like the News Literacy Project (NLP) are here to support the public and those in education and the media to become more news-literate and push back against misinformation

The NLP is a non-partisan American education nonprofit dedicated to building a nation equipped with critical thinking skills for the digital age. Founded in 2008 by Pulitzer Prize winner Alan C. Miller, the NLP offers a range of resources for educators, students, and the general public. Their mission is to empower individuals to become discerning consumers of information. Through workshops, online resources, and even a mobile app, the NLP teaches users how to:

- Identify credible sources: The NLP equips users with tools to assess the legitimacy of news outlets and social media accounts.

- Recognize bias: News reporting is never entirely objective. The NLP helps users identify and understand the perspectives influencing a story.

- Spot misinformation and disinformation: The spread of false information online is a serious problem. The NLP teaches users how to identify misleading content and avoid sharing it.

The NLP emphasizes the importance of a healthy democracy being built upon a foundation of informed citizens. By equipping individuals with news literacy skills, they aim to foster a more engaged and critical populace. Listed below are some of the NLP’s key resources:

- Checkology: A free e-learning platform with engaging, authoritative lessons on subjects like news media bias, misinformation, conspiratorial thinking, and more. Learners develop the ability to identify credible information, seek out reliable sources, and apply critical thinking skills to separate fact-based content from falsehoods.

- Get Smart About News: A free weekly newsletter that offers a rundown of the latest topics in news literacy including trends and issues in misinformation, social media, artificial intelligence, journalism, and press freedom.

- RumorGuard: A viral rumor fact checker that offers concrete tips to help you build your news literacy foundation and confidently evaluate claims you see online.

- Is that a fact? Podcast: Podcast that informs listeners about news literacy issues that affect their lives through informative conversations with journalists and other experts across a wide range of disciplines.

- News literacy tips, tools, and quizzes: Test and sharpen your news literacy skills with short activities, engaging quizzes, and shareable graphics for learners of all ages.

With the ever-changing media landscape, news literacy has become an essential skill for everyone. The News Literacy Project is a valuable resource for those seeking to navigate the complexities of the information age and become more informed citizens.

A few months ago we discussed some of the challenges presented by AI-generated content on social media, particularly in the context of misinformation and the many ways in which it is disseminated online. Fast forward to February 2024 and current events have proven that AI is not a power that can continue to go unchecked. In late January, social media platform X, formerly Twitter, was forced to block searches for Taylor Swift after explicit AI-generated images started circulating on the site. The photos were removed, but not before they were seen by tens of millions of X users. This troubling incident prompted a bipartisan group of United States senators to introduce a bill that would criminalize the spread of nonconsensual images generated by AI, but for the time being, there is no federal law regulating the production and distribution of AI-generated images.

Though there have always been various legal and ethical concerns raised by the proliferation of AI images, the rate at which this issue is growing far surpasses the amount of time it has taken humans to solve it. While lawmakers have long anticipated that AI images would complicate modern notions of privacy and intellectual property, far less attention was paid to informed consent. Addressing these legal and ethical concerns requires a multifaceted approach involving collaboration among policymakers, IT specialists, ethicists, and other stakeholders to establish guidelines and regulations that balance innovation with societal well-being and individual rights. But if the last week has taught us anything, it is that we are not without power in this fight. Ultimately, it was not lawmakers or big tech who protected Taylor Swift, but her fans. X only blocked the account responsible and suspended searches for Taylor after Swifties mass reported the images.

So, what can we do? Most importantly, we need to learn how to identify AI-generated images. This has and will continue to become more challenging as technology advances. However, there are some signs and techniques that can help us recognize them. First, AI-generated images may have inconsistencies or implausible details that are not easily noticeable. Look for abnormalities in lighting, shadows, reflections, or proportions. AI models struggle with generating realistic poses or perspectives, so be sure to check if there are odd or physically implausible positions of objects or people in the image. AI-generated images may also exhibit artifacts or distortions, especially around the edges of objects or in areas of complex detail. Pay attention to unusual pixelation, blurriness, or irregularities.

While many of these details may be tricky to spot, others are more obvious. Some AI-generated images have watermarks or signatures left by the algorithms used to generate them. Check for any unusual markings that may indicate AI manipulation. There are also online tools and services specifically designed to detect AI-generated content. Some platforms, such as Is it AI? and Illuminarty use advanced algorithms to analyze images and identify patterns associated with AI generation. Not all AI images are created and circulated with malicious intent. In fact, AI images can be quite fun to create and share, but if you ever come across photos that appear nonconsensual or explicit, it is important that you report them and encourage others to do so as well. If we all take a note out of the Swiftie playbook and work as a team to protect one another, we can contribute to larger efforts to keep AI in check.

Staying informed about political events during the age of information is crucial, especially during election seasons. While this may seem like a fairly simple task, the proliferation of social media has made it much more difficult to distinguish between credible news and misinformation online. As the 2024 election approaches, it is important that we arm ourselves with the tools necessary to navigate the information landscape effectively and avoid falling victim to fake news. To that end, we thought the start of the new year would be a great time to brush up on some of our digital literacy skills.

The first step in avoiding fake news is to verify the credibility of your information sources. Stick to well-established and reputable news outlets that adhere to journalistic standards and cross-reference information by checking multiple sources to ensure accuracy and objectivity. Be cautious of websites or platforms with a history of spreading misinformation and use fact-checking tools to verify the accuracy of claims and statements. Websites like FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, NPR Fact Check, and Snopes specialize in debunking false information. Plug-in tools for web browsers such as Media Bias Fact Check can also help flag potentially misleading content by providing fact-checking insights as you browse.

Listed below are some extra tips to help you spot mis- and dis-information on your social media feeds.

- Be skeptical of headlines

Fake news often relies on attention-grabbing headlines to lure readers in. Before sharing or believing a story, read beyond the headline and delve into the content. Misleading headlines can misrepresent the actual information contained within an article, so always read the full piece to understand the context.

Pay attention to language and tone

Pay attention to the tone and language used in news articles. Legitimate news sources maintain a neutral and objective tone, presenting facts without sensationalism. If an article is overly emotional, contains inflammatory language, or uses excessive capitalization or punctuation, it may be a sign of biased or fake news.

Don’t forget to fact check photos and videos

In the digital age, images and videos can be easily manipulated to convey false information. Before sharing multimedia content related to the election, verify its authenticity. Reverse image searches and video analysis tools can help determine if visuals have been altered or taken out of context.

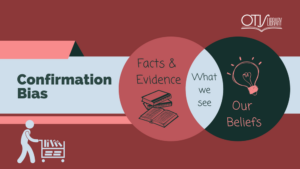

Beware of social media echo chambers

Social media platforms play a significant role in shaping public opinion, but they can also contribute to the spread of fake news. Be aware of the potential for echo chambers, where individuals are exposed to information that aligns with their existing beliefs. Diversify your sources and engage with a variety of perspectives to avoid confirmation bias.

Learn to spot misinformation in the wild

Understanding common tactics used to spread misinformation can enhance your ability to identify fake news. Look out for misleading statistics, out-of-context quotes, and the use of anonymous or unverifiable sources. Being aware of these tactics will empower you to critically evaluate the information you encounter.

As the 2024 election approaches, the importance of navigating the information landscape responsibly cannot be overstated. By adopting a critical mindset, verifying sources, and utilizing fact-checking tools, individuals can play a proactive role in combating fake news. Staying informed is a civic duty, but doing so responsibly ensures that the information we consume contributes to a more informed and resilient democratic society. The work is tedious, but every scrap of misinformation that we identify and dispose of is another step in safeguarding our democracy. Always remember that our librarians are here to help you every step of the way!

The Encyclopedia of Misinformation: A Compendium of Imitations, Spoofs, Delusions, Simulations, Counterfeits, Impostors, Illusions, Confabulations, Skullduggery, Frauds, Pseudoscience, Propaganda, Hoaxes, Flimflam, Pranks, Hornswoggle, Conspiracies & Miscellaneous Fakery by Rex Sorgatz

Happy Holidays from Otis Library! To celebrate, we thought it might be fun to take a break from the doom and gloom and offer up a more lighthearted book spotlight. The Encyclopedia of Misinformation [insert longest subtitle of all time] by Rex Sorgatz is an exhaustive historical compendium of deception and delusion. In it, Sorgatz explores heavy topics such as propaganda, hoaxes, conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, deepfakes, fanfiction, and gaslighting in a playful and humorous way. Using a series of vignettes to illustrate the points, Sorgatz raises important questions about the nature of truth and deception in the modern world. From the world of knockoff handbags to Slender Man and something called the “infinite monkey theorem,” Sorgatz demonstrates just how pervasive misinformation can be and encourages readers to be critical of all of the information that we encounter, even that which seems innocuous.

The Encyclopedia of Misinformation is available for free on Hoopla! Hoopla is a library media streaming platform made accessible to you by Otis Library. Simply download the Hoopla app, set up a free account using your Otis Library card, and enjoy a wide selection of ebooks, audiobooks, movies, TV shows, and more! Looking to learn more about how you can fight misinformation? Check out the series Finding Misinformation: Digital Media Literacy series by The Great Courses, also available on Hoopla!

Over the course of the last several years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized various aspects of our lives, from enhancing healthcare and improving transportation systems to personalizing our online experiences. However, this technological marvel has a dark side. When ChatGPT was launched to the public in November of 2022, AI became freely and openly available to anyone with an internet connection, creating unprecedented obstacles for educators on a global scale. Not only does AI discourage creativity and critical thinking, it can also be a powerful tool for spreading misinformation, amplifying rumors, and even manipulating public opinion. In this article, we will explore how AI can be employed to disseminate false information and the challenges it poses for society.

One of the key ways AI spreads misinformation is through its amplification effect. Social media platforms, search engines, and recommendation algorithms use AI to analyze user behavior and deliver personalized content. This technology is incredibly efficient at keeping users engaged and maximizing the time they spend on these platforms. However, this efficiency can also be exploited to propagate false information. Misinformation often spreads faster and wider than true information, mainly because sensational or false claims grab more attention. AI algorithms, designed to increase user engagement, may prioritize content that is emotionally charged or controversial. This can inadvertently amplify and promote fake news, conspiracy theories, and biased narratives. AI algorithms, while designed to be objective, can inadvertently propagate bias. These biases can be exploited to promote certain ideologies or worldviews, leading to the spread of misinformation. When AI algorithms favor certain types of content or sources over others, it can create echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs and filter out alternative viewpoints.

AI-driven automated bots are another potent tool for spreading misinformation. These bots can generate and disseminate vast amounts of content on social media platforms, making it appear as if there is significant public support for a particular narrative or belief. They can create the illusion of a groundswell of public opinion when, in reality, it may be driven by a small group of actors. In addition, deep learning technology has given rise to deepfakes and synthetic media, which can be used to create convincing fake videos, audio recordings, or text. These AI-generated forgeries can deceive the public by making it seem as though real individuals are endorsing or spreading false information, further eroding trust in the authenticity of media and information sources.

Addressing the issue of AI-driven misinformation is a complex challenge, but it is essential for safeguarding the integrity of information ecosystems. Listed below some ways that we can combat the spread of misinformation through AI.

Fact-checking and verification: Shake the dust off of your fact-checking skills and stay consistent. AI-generated content can be very difficult to detect, and it is nowhere near foolproof. Bard, an AI chatbot developed by the tech giant, Google, is notorious for turning out incorrect information. If you decide to experiment with AI, be sure to verify facts and key concepts to avoid spreading misinformation.

Support digital media literacy: Take advantage of media literacy programs that educate the public on how to critically evaluate information sources and encourage and support independent fact-checking organizations that aim to identify and debunk false information. Promoting digital literacy can empower individuals to discern between credible and unreliable sources and help them recognize common tactics used in the spread of misinformation.

Utilize reporting mechanisms: Keep up with reporting false or misleading content to social media platforms. Quick response to reports can help mitigate the spread of misinformation

Advocate for responsible use of AI and algorithmic transparency: AI developers and users must adhere to ethical guidelines and principles, but stricter regulations can be implemented to ensure the responsible use of AI technology. Put pressure on your representatives to implement privacy legislation and ensure that tech companies strive to make their AI algorithms more transparent and accountable. If you have concerns about the use of AI, contact your legislators and let them know.

AI is a double-edged sword, capable of both incredible advancements and destructive consequences. While it has the potential to revolutionize various industries, it also presents significant challenges, particularly in the context of misinformation. Addressing the issue of AI-driven misinformation requires a collaborative effort involving tech companies, policymakers, educators, and the public. By understanding the mechanisms through which AI propagates false information and taking proactive steps to mitigate these risks, we can hope to preserve the integrity of our information ecosystems in the digital age.

By the way, we used AI to write parts of this article. Could you tell the difference?

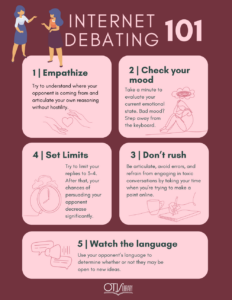

Some social media users live for a good debate, and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Sure, we don’t recommend that you spend all of your free time arguing with strangers on the internet, but there’s nothing wrong with a little civil virtual discourse from time to time. After all, calling out mis- and dis-information when you see it is an important responsibility of any digital citizen. But how does one go about “winning” an argument online, and when is it appropriate to stand down? Shown in the infographic below are 5 simple tips to help you set boundaries and avoid frustration when engaging in debates on social media.

1.) Empathize – Try to understand where your opponent is coming from and calmly articulate your own reasoning. If you are familiar with the person, try to recall any details that you know about them that may help you to determine how their opinion has formed over time and make an effort to explain how events in your own life have influenced your beliefs. This can help to establish common ground and eliminate some tension from the conversation.

2.) Check your mood – Debating when you’re in a bad mood is never a good idea. Not only will your ability to effectively communicate your opinions be diminished, but you will also be more likely to say things from a place of anger, rather than a place of reason. If you’re not feeling your best mentally, try to refrain from getting behind a keyboard.

3.) Don’t rush – Take your time when formulating a response. Rushing your responses can lead to errors, and you may even make the mistake of spreading misinformation. Slow down and take the time you need to do proper research and organize your thoughts. Hasty responses are rarely effective.

4.) Set limits – If you don’t feel as though you’re getting anywhere with your opponent after 3 or 4 replies, you may want to think about standing down. Set reasonable boundaries for yourself and stick to them. Identifying misinformation is important, but mental health comes first.

5.) Watch the language – Pay attention to your opponent’s language to gauge whether or not they are going to be open to hearing new ideas. It is perfectly okay to walk away from a debate before it begins. Your time is valuable and best spent participating in constructive debates, not petty arguments.

“The USPS package arrived at the warehouse but could not be delivered due to incomplete address information. Please confirm your address in the link. The USPS team wishes you a wonderful day!”

Have you ever gotten a message like this? Typically the “notice” is accompanied by a link to what appears to be the United States Postal Service website. The website prompts users to enter personal information like name, home address, and phone number. It then asks for a small fee for redelivery, followed by a request for credit card information. While the website may look legitimate, this type of message is almost always a scam. Unfortunately, millions of citizens fall victim to these types of schemes every year. The question is, how do they keep getting away with it?

The answer is very simple: dependability. By this point, many of us have learned how to identify and avoid getting scammed online. You may even feel confident that it could never happen to you. But what happens when the message comes from an organization that you trust? What happens when the URL appears to be legitimate, and the website appears identical to that of the real United States Postal Service? What if you have an important package in transit and don’t want to risk losing it, so you decide to pay the $6 redelivery fee, because surely one of the most dependable government agencies wouldn’t try to swindle you? Unfortunately, criminals have gotten exceptionally skilled at replicating content, meaning that they can design a website that looks and functions very similarly to legitimate websites that they know people trust.

This is an example of something called “smishing,” or the practice of sending fraudulent text messages pretending to be a reputable company or institution to persuade individuals to reveal personal and financial information. We can think of smishing as a form of imposter content, or disinformation that is created and presented using the branding of an established news agency or government institution. Imposter content is a very effective way of spreading disinformation. Let’s take the New York Times, for example. The New York Times is widely considered to be one of the country’s most trusted news sources. Considering that many individuals use the New York Times to fact check, it comes as no surprise that most readers don’t feel the need to verify information published on the NYT website. Meaning that if a well-executed imposter site pops up and begins spreading falsehoods, readers might not even notice that they aren’t reading a trusted source.

Even the most cautious internet user is at risk of falling for imposter content. When visiting websites (especially those that you have navigated to from an outside link) be sure to take a look at the branding. Does the logo seem distorted? Are the colors the same? Also pay attention to the content. If it is a news site, do you notice any sensational headlines or photos that appear to have been manipulated? Always do a quick fact check if you are looking at a screenshot of a news article. Content creators will often insert screenshots into their videos. These screenshots can easily be doctored to make them appear to come from a website like CNN or the New York Times, so it is important to verify that they are legitimate. Finally, never enter your personal information on a website that you did not go to directly. (i.e., do not follow a link from an unverified text message.) If in doubt, try entering some of the language from the text or email that you received into a Google search. If the scam has already been reported it will more than likely show up in your search results. As always, don’t hesitate to contact your local librarians with any questions!

The Fight for Privacy: Protecting Dignity, Identity, and Love in the Digital Age

Danielle Keats Citron

W. W. Norton & Co.

Intimate privacy is a precondition to a life of meaning. It captures the privacy that we want, expect, and deserve at different times in different contexts. At its core, it is a moral concept.

Danielle Keats Citron, 2022

This month we will be taking a short break from mis- and dis-information content to focus on internet privacy with a new book spotlight! Over the course of the last three decades, stunning technological advancements have muddled the modern definition of privacy, prompting experts to reimagine and redefine what privacy means in a world where a person’s entire life story can be pieced together using digitally collected data alone. And it’s not just the information that we post consciously. Data is harvested from every app we download and every website we visit to be used by corporations to better target their ads. Now, the ethical implications of this expansive digital surveillance system have been called into question yet again with Danielle Keats Citron’s 2022 book, The Fight for Privacy: Protecting Dignity, Identity, and Love in the Digital Age.

Citron, professor of law and privacy expert, focuses on a concept that she calls “intimate privacy.” Intimate privacy, she explains, refers to the social norms that protect the more intimate aspects of our lives, such as our health, gender, close relationships, and sex. The invasion of this privacy, Citron argues, can stunt the development of our self-identity and threaten our intimate relationships. As dystopian as all of this sounds, Citron believes that through advocacy, we will eventually be able to strike a balance that allows us to enjoy the benefits of technology while keeping our intimate privacy protected. The tricky part is that this balance hinges upon a collective effort to convince lawmakers that intimate privacy is a civil right that should be guaranteed to all citizens. As is the case with mis- and dis-information, the responsibility belongs to us.

“This is a terrific, though terrifying, exposé about how often our intimate activities and intimate information end up on social media. Professor Danielle Keats Citron makes a compelling case for a ‘right to intimate privacy’ under the law. This beautifully written book deserves a wide audience and hopefully will inspire needed meaningful change in the law.”

Erwin Chemerinsky

University of California, Berkeley School of Law

Visit our online catalog to reserve a copy of The Fight for Privacy.

“The emotional appeal of a conspiracy theory is in its simplicity. It explains away complex phenomena, accounts for chance and accidents, offers the believer the satisfying sense of having special, privileged access to the truth.”

Anne Applebaum, 2020

The faked moon landing, chemtrails, the death of Princess Diana, a chamber of secrets hidden behind Mount Rushmore, Aliens in Area 51. Do any of these tales sound familiar? You probably recognize them as popular conspiracy theories, or conjectures that imply that an organization of influence is responsible for a major event or phenomenon. Most of us have encountered a conspiracy theory at least once in our lives, whether it be in jest or in one of the shadier corners of social media. But while we might understand what a conspiracy theory is, knowing what the term means is just the tip of the iceberg. The bigger, more consequential question is: how does a conspiracy theory come to be, and how can we use that knowledge to identify conspiracies before they gain traction online?

In June of 2020, tens of thousands of social media users were exposed to the sensational claim that Wayfair, a popular furniture and home goods firm, was using high-priced cabinets as a front for a child-trafficking ring. According to the claim, Wayfair had been using cabinets priced in the thousands to sell children directly from their website. Screenshots from the Wayfair website showed a description of the furniture pieces, most of which were given human names such as Samiyah, Annabelle, and Allison. Some of the cabinets were priced as high as ten thousand dollars. News of the alleged human trafficking ring, which originated in the QAnon community, quickly spread through lifestyle influencer and parenting communities before breaking into the mainstream. For the first few days, the internet was divided. Some believed the theory to be plausible, while others felt that it was too sensational to be true. Wayfair denied the allegations, explaining that the price of their industrial cabinets was comparable with other retailers, as was their decision to assign the furniture human names. Still, the Wayfair conspiracy theory has endured. Why?

In her book, Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism, Anne Applebaum points to the inherent simplicity of the conspiracy theory to answer this question. Humans create outlandish theories to explain away things that they don’t understand or can’t come to terms with, such as the death of a beloved celebrity or a natural disaster. In other cases, such as that of “Wayfairgate,” conspiracy theories are born out of social isolation. Believers of the Wayfair conspiracy claimed that exposing the company was up to “the people” because the mainstream media was pushing it under the rug. This widespread amateur investigation gave people a sense of purpose and created the illusion that they were part of an inside operation to bring down the alleged perpetrators. The recent influx of misinformation that now circulates online has only exacerbated the intensity of conspiracy theories, many of which pose a real threat to democratic institutions and society as a whole.

The good news: conspiracy theories are fairly easy to identify because of their shock value. Take in the claim and sit with it for a while. Does the claim seem realistic, or does it feel hyperbolic? Is there any solid evidence to back it up? Where did it originate? Who are the people or groups disseminating the claim? Do they have any credentials? Dust off your fact-checking skills and seek credible sources. If you can, share what you find with your friends and followers on social media. Sometimes, a simplified, reasonable explanation of an event is all it takes to quell the spread of conspiracy theories, but be aware that some people will simply not be convinced that a conspiracy theory is a farce. In these cases, it is best not to engage. Instead, focus your energy on getting ahead of misinformation through reason and research.

Earlier this spring, TikTok user Allie Casazza made a bold claim to her nearly 13,000 followers: I just cured my daughter’s strep throat homeopathically. Casazza, an influential blogger and self-proclaimed “mom coach,” went on to say that she was able to cure her teenager’s severe case of strep throat with potato juice. Yes, you read that correctly, potato juice. Casazza, who has no medical background, is not the first TikToker to assert that potato juice can “cure” serious illnesses, including but not limited to: liver disease, stomach ulcers, and arthritis. As you may have already guessed, there is no substantial evidence that potatoes treat strep throat, a bacterial infection that if left untreated can lead to kidney inflammation or rheumatic fever, a serious condition that can cause permanent damage to the heart.

Casazza’s video quickly caught the attention of outraged healthcare professionals, who took to TikTok to express how dangerous Casazza’s claim was and demand that the video be removed from the platform. The consensus among TikTokers in the medical field was overwhelming: failure to administer antibiotics to children with Strep A can have life-threatening consequences, and under no circumstances is potato juice a suitable substitute. This is not the first time that medical misinformation has circulated on TikTok and Instagram, and it certainly won’t be the last. If you think all the way back to November’s article on confirmation bias, you may recall how exaggerated claims often begin in isolated online communities. This is exacerbated by TikTok’s strikingly accurate algorithm, which continuously feeds users content of a similar nature. These information bubbles can become so intense that members quickly begin to reject any piece of contradictory evidence and will block users that challenge them. It’s a fast track to radicalization, and it’s happening every day.

In 2013, a PEW foundation survey revealed that 6 out of 10 Americans turn to the internet to find the cause of their own medical conditions. To make matters worse, 35 percent of those who found a diagnosis online did not consult with a medical professional for confirmation. Those figures are undoubtedly higher in 2023. At this stage, it is unrealistic to expect Americans to simply stop using the internet to find information about their health, but we should exercise caution, especially on social media where Western medicine is often disparaged by users who favor a homeopathic lifestyle. Listed below are some simple ways that you can use the internet responsibly to make informed decisions about your health.

Be sure to crosscheck your information

You can put those self-guided research skills to work and search for peer-reviewed literature, but always be sure to consult with a medical professional (or several) before taking OR denying any new medications or supplements.

Evaluate your own digital community

Have you fallen into an information bubble? Are prominent members of your community (influencers, popular TikTok creators, etc.) legitimate? If a content creator claims to be a doctor, be sure to Google their name and verify that they are licensed and affiliated with an accredited medical institution. Venture outside of your comfort zone and evaluate what others are saying around you.

Be on the lookout for profit motives

Most popular content creators are going to try to sell you something at least once. This year, the brand Bloom Nutrition has exploded on TikTok and Instagram, with creators on all sides of TikTok promoting their Greens & Superfoods powder. The brand claims that the powder aims to aid in digestion, decrease bloating, and boost immunity, but it lacks clinical research support and proven results. TikTok creators get paid for their promotion of the product, the brand sees increased sales, and the consumer is left with a product that doesn’t necessarily harm them but doesn’t help them either.

Sander van der Linden

W.W. Norton & Company, 2023

Last month, social psychologist Sander van der Linden’s book Foolproof joined the Otis Library’s nonfiction collection. Foolproof, the culmination of decades of research and lived experience, aims to tackle the misinformation phenomenon at the root. To do so, van der Linden asks questions such as, why is the human brain so vulnerable to misinformation? How does it spread throughout online communities? And most importantly, how can we stop it? Likening the spread of misinformation to a virus, van der Linden argues that we must shift our focus from what we may think of as antiviral remedies, such as fact-checking, to inoculation. Drawing upon basic principles of psychology, van der Linden provides readers with practical defense strategies and tools for fighting misinformation spread.

“An optimist and fine writer, van der Linden, professor of social psychology at the University of Cambridge and an expert on human belief systems, explains why humans accept something as true or false and how they can fend off misinformation. He begins by explaining why we are susceptible, discusses how falsehoods persist, and then explains how to inoculate ourselves and others. Insightful, convincing, instructive reading.”

Kirkus, 2023

Visit our online catalog to reserve a copy of Foolproof.